A shiny brass trident carrying the hand drum of Shiva, god of destruction, absolute wisdom and bliss, is trembling impatiently in the windscreen. Above and below the narrow serpentine mountain road, towering Himalayan cedars block the view, as we rumble along the potholed tarmac towards the Jhanna waterfalls. Here and there colourful villages perched on steep terraced slopes, flash between the dark tree trunks. At the tall waterfalls cascading from high meadows and snowclad peaks, we get out and put on our backpacks.

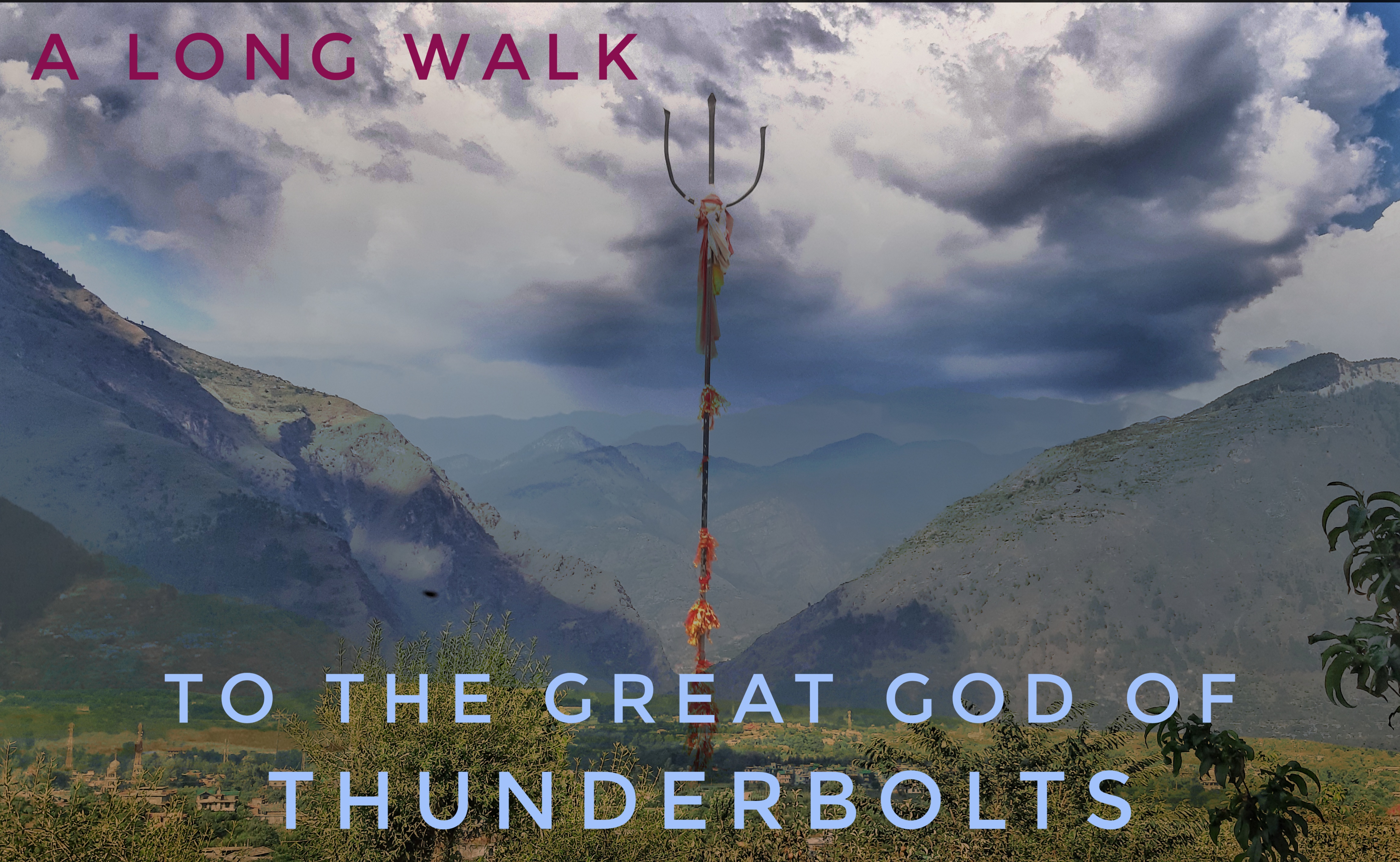

Across the wide Kullu Valley, from the high and narrow Bhou Bhou pass, an ominous mass of clouds is forming, gusts of wind blow dust in our eyes. “They call it the storm maker” I say dramatically as we start walking into the forest. It begins to rain. Real Shiva weather. “I brought a thermos of chai” she says. We have a long walk ahead along the unused dirt road, running just below the ridge of the densely forested mountain range terminating at one of the most venerated Shiva temples in this area; Bijli Mahadev, Thunderbolt Shiva.

This temple marks one side of the narrow entrance to the long wild Parvati Valley. At the end of the valley an ancient glacier gives birth to a holy lake—the source of the roaring Parvati River. At the head of the valley—according to legend—Shiva sits on his mountain throne in unmoving meditation. Actually, every peak is the abode of Shiva. He represents the unmanifest resting consciousness, and his consort, the goddess Parvati, is shakti; the restless, fiery fuel of manifestation. Their union creates this world.

My hiking companion has not yet seen the mountainous Parvati Valley that lies hidden behind the tall ridge. The idea is to see the June full moon rise above its snowy peaks.

We barely stop talking the whole day—about astronomy, the golden age of Islamic culture, her time in Andalusia, my life in Cairo, the Silk Road, and the periodic table. The landscape changes from exposed rocks to deep green forest inhabited by bears and the presence of monkey eyes. Showers come and go.

But our pilgrimage is a skip and a jump compared to the long trek to the holy lake near the head of the Parvati River. In the short alpine summer, Sadhus—wandering ascetics, devotees of Shiva—walk the way to the holy lake. In the wide meadows below the glacier, they plant their most prized possession in the soft soil to mark the end of their pilgrimage—their Shiva trident. There on the bank of the lake, a small forest of tridents with flapping red ribbons has grown.

This high lake sets the beginning and end of my novel—Like Two Rivers—the still source of the roaring river unfolds the story.

The Parvati Valley is where I met a person that changed my life forever, and who, though only appearing once in the novel, is the lodestar of the complex story.

Meandering across the planet the novel encompasses much more than this remote Himalayan valley. Though today, as often happens in these mountains, talk and thought turns to Shiva. It is after all the goal of our pilgrimage this dark and cold day of June to reach his temple.

The Shiva temple, Bijli Mahadev, occupies a peninsular mountain top also long venerated by Tibetan Buddhists, whose newly build yellow monasteries dot the populated and fertile Kullu Valley below. It is said that this holy mountain is mentioned in the Upanishads—ancient Hindu scriptures—and whoever lives in its shadow will gain enlightenment. On a high ridge down valley is perched a famous Vishnu temple and across valley sits one of the rare temples to Brahma. The area verge on Hindufied tribal shamanism, where every village has its own god, and animal sacrifice—magic and oracles are part of everyday life; this triangular positioning of three chief Hindu gods is unusual.

This trinity of gods—Shiva the Destroyer, Brahma the Creator, and Vishnu the Maintainer—spans the pastoral Kullu Valley framing the wedge-shaped entrance to the wildness that is Parvati Valley.

Now and then the sun peeks out as we ramble joyfully through topics like iridium sediments, grand extinctions, family stories, the concepts of distinct cultures and nation states. After many hours we stop for lunch on the windswept slopes. Around us cows huddle, patiently waiting for the weather to change. I point down to the pale ribbon of the river. “Just there,” I explain while putting on my raincoat, “one of the main characters of the novel, after restlessly searching the planet for a lifetime, steps off a night bus on a dark monsoon morning and remembers what he was looking for all this time; peace.” Off course that person was me. We circle back to talking about Hindu gods.

In Hindu cosmology three basic forms of energy or subtle building blocks constitutes manifestation. They are called gunas. The three gunas represent the evermoving nature of the creative, the unmoving nature of stillness, and the even nature of balance. Some have compared these principles to —electrons, protons, and neutrons or Father, Son and Holy Ghost, but in Hindu mythology they are represented by the trinity of gods—Brahma, Shiva, and Vishnu. It is paradoxical that it is not Brahma, the creator, who is considered the highest god, nor is it Vishnu, the maintainer. The title of Mahadev—the Great God—belongs to Shiva, who in this trinity represents the unmoving force or guna. Yet, he is also the god of destruction. How does an unmoving meditating god destroy? What does he destroy? And did we not just say earlier that he, with the manifesting force of Parvati, creates the world? Shiva, as the greatest of gods, is unfathomable to our logic minds; he has 108 names and surpasses futile attempts of analysis or assigning of archetype. In a way he is every aspect of this world, and at the same time beyond it and untouched by it. Shiva is seen as the great yogi, the eternal teacher of mankind and in essence he is pure undifferentiated consciousness. Out of this pure consciousness multiplicity appears like a mirage.

In my novel, Like Two Rivers, the main characters come from diverse cultural, social, and religious backgrounds. They are in their own way all searching for something that they can barely grasp. This unconscious longing takes them across borders and continents. Compelling them, in accordance with their conditioning, to change name or identity, to become refugees, wives, immigrants, husbands, and pilgrims. Some die on the way, killed by their own ideas, others settle for dissatisfied security. Some, driven by an insatiable thirst for freedom, keep moving and enquiring. Through the narrative, a subtle thread of veiled wisdom is woven by a handful of half-hidden characters: a fabled Himalayan hermit, a secretive Sufi woman, a vagabonding human trafficker, and a dishonoured philosophy teacher.

“The wheel of this world spins so fast, that if you had to put your finger on it, you’d have to become perfectly still,” a wise man told me. This is one of the ways in which Shiva becomes the destroyer.

In Hindu philosophy the act of spiritual quest at its core distinguishes the changing from the unchanging, the constant from the wavering. What is constant cannot be changed or destroyed. Shiva is the destroyer of the always changing. That which is always changing is this world, and its wavering nature makes it ungraspable and illusory. Shiva is an eternal mountain peak, sitting in deep unwavering meditation—observing eternity. Shiva’s truth is wordless and constant, and this knowledge dismantles the idea of a solid and material world; through stillness he destroys the moving illusion. He is the perfect yogi.

It has changed into late afternoon. We talk about genetic engineering and our knees hurt as we, through a flock of sheep, turn off the path and scramble up through the ancient forest. Then, as we climb over a grassy knoll on the rocky ridge, there she is; Parvati Valley. Wild, rugged, steep, and narrow. Crowned by towering snowclad peaks ending in rocky spires, pyramidal and jagged. Deep below the Parvati River forever rushing away from the distant glacier, her eternal source. Her Shiva. Some kilometres ahead along the undulating forest ridge, we see on an open alpine meadow the unassuming temple of the Great God of Thunderbolts. Bijli Mahadev. Shiva.

“I can’t believe that this was hiding just behind the hills I see from my house!” my friend says and sits down mesmerized. Here each valley is a different world. The view is otherworldly, but it is too cold to remain.

We make our way along the ridge, through sacred groves, past altars to unknown gods from unknown times and at dusk we finally arrive at the small wooden temple. No moon is seen. Thick clouds hang low. We take off our shoes, walk over the cold stones with our sore feet and enter. A cracked black stone lingam—a symbol of the power of creation and of Shiva—sits silently in the dark sanctuary. No one knows its age. It is said to have been struck by lightning, scattered in the valley, and reassembled several times. We strike the temple bell, sit down, and close our eyes. As the ring dies away a deep stillness envelope us. We have arrived.

Like Two Rivers will be published before the end of the year.

- The Beginning. Chapter from Like Two Rivers

- Seeking Sage

- Lost in the Mind; A Medieval Madhouse in Aleppo

- Walking on the edge of Knowing and Not Knowing

- Language and Reality