“Madness is an inability to know dream from reality “-Ibn Sina

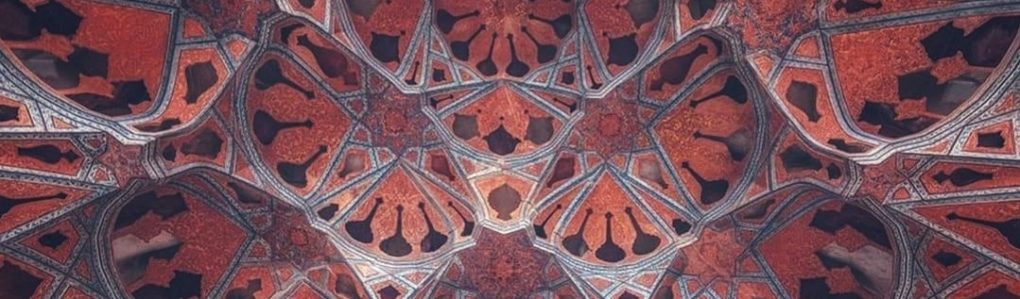

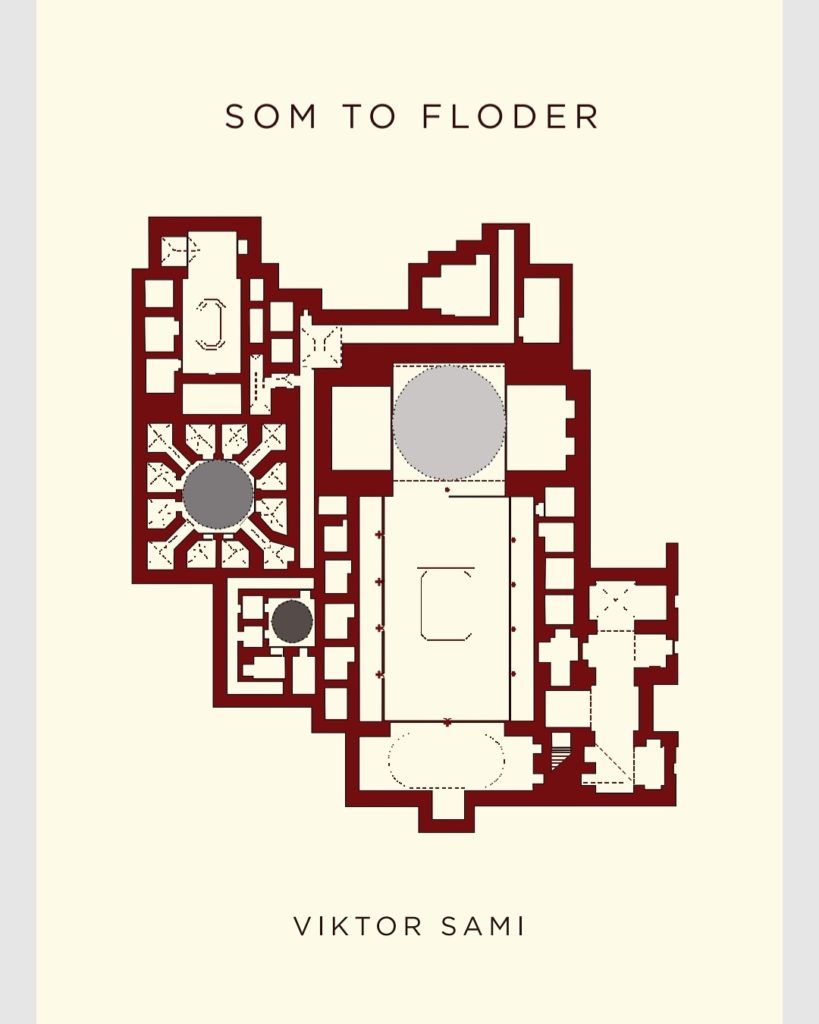

Aleppo, Syria, December 1984: “Unexpectedly Nabil stepped out into an octagonal courtyard. In the centre sat a beautiful star shaped sandstone basin. Two overlaid squares turned around a shared centre. Eight-pointed. Around him there were twelve dark door openings. Above them were twelve black portholes. He had never seen anything like it. Everything was built in stone. Again, the reliable and solid aesthetics of the Mamelukes. He could have stumbled into a Sufi monastery, a zawiya. But it did not look like the ones in Cairo and he thought of himself as an expert of everything that caught his interest. Through a circular aperture in the top of the tall dome, he saw above him the distant paleness of the Aleppo sky.

Up there somewhere the doves would be, for even though he could not see them, their sad cooing was now very close. When he looked down again, he suddenly no longer knew through which door he had entered and as he disorientedly looked around, he noticed that the twelve openings were not evenly spaced on the eight walls. Twelve was not divisible by eight. On four walls the doors sat close, in pairs, two on each wall. But the four interspersed walls only had one door each. One door, two doors, one door, two doors. So, from where did he come?”

Excerpt from the novel Like Two Rivers, by V.J. Sam.

In the early Islamic world, mentally ill people were not seen as evil or punished by God, but often as those to favour with kindness, protect, and relieve of worldly duties. Laws were enacted to ensure their rights. In the ancient city of Aleppo, Syria a bimaristan—Persian word meaning “hospital”—was built in 1354 by Sultan Al Kamili; Bimaristan Arghun. The recent siege (2012–2013) of Aleppo severely damaged this hidden gem that stood over 600 years in the amazing old city along the Silk Road.

In the novel, Like Two Rivers, it is in Aleppo where Egyptian Nabil, due to complex family demands, has exiled himself. Nabil falls in love with a man who looks alarmingly like himself; Ehab, a stateless orphaned Palestinian.

As their relationship becomes serious, necessity forces them to protect their love. They spin a withdrawn magic world of their own, where they begin to compare themselves to the medieval Sufi poet Rumi and his teacher Shams. They are both Shams and both Rumi. Due to the fascination with each other, the painful wish to become someone else, and fuelled by their mutual denial that they look like brothers—they unconsciously begin to exchange identity.

One winter morning Nabil walks through the old Byzantine bazar. Lost in speculation he enters a dark gateway and finds himself lost inside an ancient narrow beautiful maze. A low sorrowful murmur echoes beneath the elaborate masonry domes, through the octagonal courtyards and complex corridors.

Nabil, who constantly seeks a secret code believed hidden within the structure of the world itself, now finds himself caught in this maze. But his anxious attempts to calculate the way out—using his knowledge of math, architecture, and mythology, leaves him even more confused.

As he steps out of the maze, a sign indicates that the place is a bimaristan, a medieval mental hospital. This throws him into a whirlpool of speculation. Cold and exhausted he returns to the small hotel room he shares with Ehab. Unable to share the unsettling experience in the bimaristan with Ehab, Nabil cannot stop pondering on its significance.

The Greeks, whose earlier writings were thoroughly studied by early Islamic scholars, had viewed mental illness as demonic possession, punishment by God. Europe, for many hundreds of years to come, would share this idea and see it as a common sense approach to disease. But in the early Islamic world the great scholar and father of medicine, Ibn Sina/Avicenna (980–1037 CE), and his contemporaries studied mental disease and painstakingly documented numerous conditions such as anxiety, melancholia, schizophrenia, paranoia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and hallucinations.

Ibn Sina was one of the most significant thinkers and scientists of the Islamic Golden Age and produced a five-volume encyclopaedia: The Canon of Medicine (Al-Qanun fi’t-Tibb). It was used as the standard medical textbook in the Islamic world and Europe up to the 18th century.

As part of a powerful wave of rational approach to natural phenomena, he introduced about thirty medicinal herbs for treatment of depression alone, many of which have been proven effective by modern medicine.

By the 8th century CE, major Islamic cities had hospitals in the modern sense of the word. Bimaristans were built in Cairo, Baghdad, Aleppo, and Damascus—well-staffed, cloister-like havens designed to calm the spirit. The treatments, unlike those in contemporary Europe, were based on a solid understanding of an individual’s imbalance and included therapies using medicines, music, water, and massage, as well as occupational therapy, introspection, and nutritional programs.

Ibn Sina saw a connection between the body and the mind and was the first to put into words the idea of psychosomatic disease. He explored the relations between organs and mental disease and speculated on body chemistry and mental health. Later, Ibn-Khaldun (1332–1406 CE) proposed a revolutionary idea for that time; that a person’s local environment and social conditions shaped their personality.

Cultural definitions of normality, love, wisdom, and identity are themes within the book—Like Two Rivers.

So, as winter in Aleppo creeps colder and rain sets in, Ehab begins to argue that their relationship is wrong and punishable by God. Nabil, whose mind has experienced this phase before, waits for it to pass; he does not believe that this idea comes from Ehab himself.

Then one day Nabil finds Ehab has vanished and taken Nabil’s travellers cheques as well as his fake Greek passport. Nabil is left with Ehab’s rudimentary Palestinian travel document, his Laissez-Passer. He guesses that Ehab, posing as him, is headed for Istanbul seeking European visas.

Nabil realises he must catch him before he crosses into Europe. Forced to pose as Ehab, he sets out driven by love and a hidden longing for revenge through the winter rains to the Turkish border.

A mad maze of a search based on assumptions ensues.

Two identical men with fictional identities struggling to restore a freedom the world will not allow.

The novel, Like Two Rivers, by V.J. Sam will be published at the end of the year.

Out there, beyond ideas of wrong and right action, a field exists.

That is where I will meet you.

When the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to be spoken off.

Rumi.

- The Beginning. Chapter from Like Two Rivers

- Seeking Sage

- Lost in the Mind; A Medieval Madhouse in Aleppo

- Walking on the edge of Knowing and Not Knowing

- Language and Reality

- The Beginning. Chapter from Like Two Rivers

- Seeking Sage

- Lost in the Mind; A Medieval Madhouse in Aleppo

- Walking on the edge of Knowing and Not Knowing

- Language and Reality

Like Two Rivers, a novel

About the book:

A philosophical adventure with multiple storylines crisscrossing back and forth from the 1960s to the late 2000s—the rich narrative follows the paths created by the longings of a diverse band of multicultural seekers, immigrants, rebels, artists, and misfits as they pursue the elusive golden promises of their own imaginings. This insatiable longing takes the reader from the high Himalayas of India to Cairo, through Istanbul on to Aleppo, Bucharest, Copenhagen, and Paris and back again. The search for answers causes the distinct strands of the achronological narrative to gradually intertwine or unravel, revealing unexpected insights, new riddles, or even deeper confusion. The central question is: If life has meaning, where is it to be found?

The story resembles a symphony, starting with a simple piano, then the addition of layered sound as more instruments come in, becoming an orchestral piece that reaches a long and exhilarating crescendo, ending with the fragile but clear tone of a violin as we—the reader-witness—return to the beginning, to innocence through a process of catharsis.

In Like Two Rivers, the unusual lives of the protagonists are portrayed in intimate detail, as they create, derail, and entangle their lives erratically across continents and through different times. The atmospheric settings are key entities acting as timeless companions of the perpetual seeker moving through ancient towns, along holy rivers, over bridges and up mountains. A wistful sense of irreversible loss pervades the story as homes, loved ones and countries are lost to linger as haunting memories.

Watching from the shadows, a handful of obscure yet pivotal sages, seers, mystics, and hermits from disparate traditions gently nudge and advise those with the ability to listen. At times, even a stray dog becomes a guide.